Veteran & EMS Doctor Shares How Healthcare Workers Are Suffering Moral Injury, Not Just Burnout

Written by Melissa Schnekman, MPH, MSJ

Caitlin McCord Delaney, Millennial, Combat Veteran, and Emergency Medicine Doctor

The War in Healthcare Is Still Raging

When Caitlin McCord Delaney, MD, sees her patients, she likes to see them fully as human beings rather than as numbers or disease conditions. She loves to hear their stories, connect with them, and figure out their needs.

At the age of three, inspired by a Halloween costume, Delaney’s career aspiration was to be an angel. For those of us who know her well, as friends and family do, I would argue to say she ultimately chose that career path, when she decided to become a doctor, especially one that would serve in the US Navy during the battle against ISIS.

She was the first in her family to pursue medicine, which she liked because it was at the intersection of evidence-based science and the creative arts (mostly the art of communicating and understanding others is what appealed to her). As time went on, she discovered her passion was in emergency medicine where adrenaline, which is what focuses her, often runs high.

“When something occurred that was life or death, I knew I was exactly where I needed to be and everything other than doing the right thing melted away. I felt like I was surrendering myself and something else was working through me,” Delaney said. “I loved the human element of the ER, where I saw what it means to be human; to endure physical failure, experience extremes of emotion, and feel the loss. But also, to fight for survival and to love.”

She knew that choosing the highly deployable field of emergency medicine meant committing herself to be in harm’s way in combat zones. But that’s what Delaney wanted, and after joining the military in her last year of college at Harvard, the US Navy provided her the funding to pay for medical school tuition at Emory University.

“I’ve always wanted to run towards whatever I see as the biggest problem,” Delaney said.

It’s a desire that during her military service and fighting on the front lines of the COVID-19 pandemic, has served her well.

Delaney (center left) with her Navy medical and Army aviation colleagues at their forward base in Iraq.

Practicing Medicine in Mosul

Service runs in Delaney’s blood.

Her grandfather was a World War II fighter pilot and member of the Explorers Club for his flight to Antarctica in which one of his missions included flying penguins back to the San Diego Zoo. There is actually a place in Antarctica named for him (Kelly Plateau).

Delaney believes some of her sense of adventure comes from him.

Other family members have also committed their lives to service—inside and outside the military. Her brothers were both submarine officers, her uncle is a retired Navy Admiral, and her cousin is a helicopter pilot, while her parents served in different ways, as a public school teacher and a government attorney.

As an Emergency Physician in the military, taking care of those who dedicated their lives to keeping us all safe, Delaney deployed to a tent hospital in Iraq with the Army during the battle against ISIS in Mosul. There, she and her team treated some US military members, but even more Iraqi military members.

They scooped them up from the Iraqi side of the base in their ambulance, which she wrote the protocols for, with a pistol strapped to her thigh wearing 45 pounds of body armor in 115-degree heat. She brought them back with her Corpsmen (military medical technicians) and continued leading their resuscitation with the rest of her team – an Anesthesiologist, Trauma Surgeon, Orthopedic Surgeon, Nurses and more Corpsmen – now present in the tent.

“I climbed onto helicopters slipping on blood, pulled people off, put them in the ambulance, and brought them back to our tent, where we were sometimes fired upon by ISIS during rocket attacks,” Delaney said. “I worked around cultural barriers that said I shouldn’t be the one doing this, because I was female, as gracefully as I could.”

“It was a tough but incredibly rewarding deployment,” she reflected.

They had to be creative when necessary. Delaney even had to learn to treat military working dogs under remote direction from veterinarians, as they didn’t have a vet on base.

“Another time, we lost electricity and used our phone flashlights to see for surgery and a crockpot as a blood warmer,” she said.

Delaney loves to improvise, relying on herself, her courage, and her flexibility.

“I really do love adrenaline, danger, and emergencies,” she said. “My colleagues in emergency medicine do, too. That’s why the pandemic has been so interesting.”

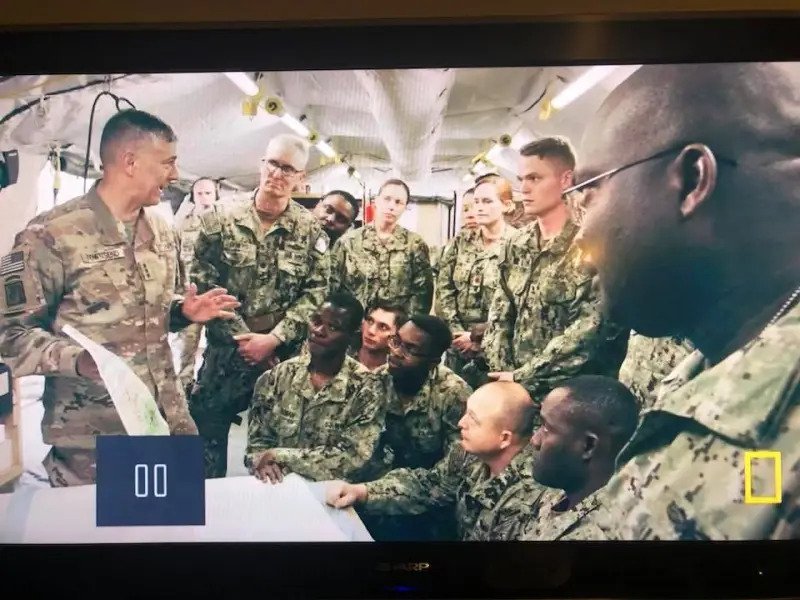

Delaney (center right) listening to a high level brief from Lt General Stephen Townsend, Commander of the Combined Joint Task Force – Operation Inherent Resolve on a visit to their hospital tent outside Mosul. Featured on National Geographic’s “Chain of Command” series.

The Worst Night of Deployment

One night, Delaney was called to evaluate an Iraqi soldier who had been shot in the calf; he was in the back of a pickup truck. The Rules of Engagement —an international-level decision on which patients they would take from Iraqi lines over the border into the US base to use resources for – had been made very clear to her and her fellow soldiers.

“There were many reasons for the Rules of Engagement, all of which I understood, including allocation of resources, medical system capacity, ability to transition to care, sustainability of the local medical system, etc,” Delaney said. “We were supposed to treat Iraqi patients with imminent life, limb, or eyesight threatening conditions to stabilize them before sending them on to more definitive care within their own country.”

She assessed the soldier’s calf and his wound looked clean through and through. He had good pulses and the bleeding had stopped, and his friends confirmed it hadn’t come from a weapon that can cause a great deal of invisible tissue damage. So, she concluded he wasn’t at risk of life, limb, or eyesight loss.

Delaney learned he was going to an Iraqi Hospital that was an hour away and gave him pain medicine for the trip. But as they started driving away, he begged her to stay.

Her interpreter translated that the Iraqi soldier was worried that there wouldn’t be enough pain medicine or antibiotics, or good enough surgeries to care for him where he was being taken. He wanted to go to the US tent, and he was terrified.

“I made so many triage decisions like that during my deployment – it’s part of the job – but this was a case where I felt clearly that the rules of the system were hurting the person in front of me,” she said. “I wanted to take care of him, and I knew how, but I couldn’t. His eyes were haunting.”

That was the worst part of Delaney’s deployment, and it is what she says she has been experiencing every day, many times a day, throughout the COVID-19 pandemic working in hospitals not abroad but at home on US soil.

Now, it isn’t just one set of haunting eyes that she sees, but hundreds, if not thousands.

Delaney calling home to her family early on in the pandemic, wearing her N95. Due to PPE shortages, it was not the size she had been fitted for.

Moral Injuries Add Salt to the Wounds

If Delaney could use five words to describe what her life has been like since the pandemic, she would use one set of words five times and that would be: “moral injury.”

While she hesitates to speak for all of her colleagues in medicine, unfortunately, she speaks for a lot of them. There have always been system-wide issues in healthcare – especially in the safety net which is the ER – but healthcare workers have never been pushed to the point of experiencing so much moral injury.

“I think that’s the part that’s hard for the public to understand when we talk about how nurses and doctors are considering leaving clinical practice,” Delaney said. “When you hear burnout, I think sometimes you think too many hours or too much stress. That exists, but the real problem was not being able to help those in front of me in the way I thought they deserved to be helped.”

To make sure she wasn’t overreacting, one time she decided to try to keep track of the number of moral injuries she experienced just in one of her nine-hour ER shifts. She counted eight instances in just the first hour.

“The confirmation was heartbreaking so I stopped counting to power through my shift.”

During the Omicron surge, when she arrived at the ER one day, she found 95 patients in the waiting room. “That was an atypical day, but emergency department (ED) crowding has not been atypical, unfortunately.”

What are the effects of emergency department crowding? She shares stories collected from colleagues across the country:

An elderly woman had to have a palliative care consult in the middle of the waiting room, a young female required a covered vaginal exam in the ambulance doorway to make sure she wasn’t bleeding out, a gentleman with a broken hip who had to sit painfully in a chair all night before going to the operating room the next day because there were no hospital rooms, or physical beds, or pillows, or any other space for him; even closets and bathrooms had already been creatively filled with patients.

A medical student who had a spinal cord mass, causing her to lose sensation in her hands, was sent home from the hospital for a third time, after waiting in the ED all night, because there were no operating rooms available to treat her and prevent progressive disease.

A family member of hospital staff had cut off his thumb with a saw but still had to sit in the waiting room holding his thumb because any available doctor or nurse was busy resuscitating other patients. Patients had medications ordered, but nursing staffing shortages were so severe they could not get to them for hours.

Dr. Delaney with her youngest daughter, who was born in 2021.

“It’s painful to look in someone’s eyes and see that hurt. No amount of yoga or resiliency training, both of which are good things, will matter if I still have that moral code, and I can’t act in alignment with it,” Delaney said.

She is very clear that this is a nationwide problem, with geographic areas that are experiencing more or less at any given time.

“I’m very fortunate to have worked in a healthcare system that handled the pandemic well and came up with a lot of creative solutions. I’m so proud of the people I work with, but they maxed themselves out,” Delaney said. “The US healthcare system got pushed to a point where disaster became so institutionalized, that the system began hurting the humans on both sides of the equation.”

Delaney recounts her personal struggles during the pandemic, which have included not only working on the frontlines, but also having family members who were medically vulnerable, ill, and passed away.

Like others around the country, she brought COVID-19 home to her family in March 2020 and experienced times when she could not access childcare for her daughters. Delaney was also pregnant and had a baby during a COVID surge. At the same, she also had a husband who was on the frontlines with the National Guard.

“I’m really incredibly grateful that life outside the hospital feels better now, but the ER still looks like a scene from Pearl Harbor some days with too many hall stretchers crowded together,” Delaney said. “There is a lot of need with people sicker because chronic care was delayed and there is more anxiety, drug, and alcohol use. And now there is a staffing crisis.”

“The healthcare system still feels like a war…a real one,” she added.

Delaney’s husband, CPT Mike Delaney, was also deployed in Iraq at the same time, at a different base except for a two-day period.

Empowering Change

Finding the silver linings in the darkness of the COVID-19 pandemic, no matter how challenging, is what keeps Delaney moving forward to serve others.

Delaney’s husband, CPT Mike Delaney, was also deployed in Iraq at the same time, at a different base except for a two-day period.

For her, the contrast between what she has seen on the battlefield in other nations and on the frontlines of a pandemic inside US emergency rooms has provided a backdrop for identifying the types of changes needed and sparked ideas for how to make them possible.

“I think the military is good at recognizing that moral injury is a real and important phenomenon, that people should be rotated in and out (i.e., there should be backup teams), and that rapid cycling between a deployment and family life is difficult and should be minimized,” she said.

For Delaney, she has always felt compelled to run toward the biggest problem and use her skills to help solve it.

“Right now, our biggest problem is the healthcare system, and the loss of good people from it,” Delaney said. “People in care fields need appropriate time and resources to be able to alleviate the human suffering before them. So, that’s what I’m going to work on.”

It’s a path that’s helped her find a new future for herself, and she hopes for many others.

Learn more about Dr. Caitlin Delaney’s work on the frontlines of the COVID-19 Pandemic, and how it has led her to pursue a hybrid career changing the healthcare system for the better, in part 2 of her story in YMyHealth’s COVID-19 Stories from the Field series.

This story is a part of YMyHealth’s COVID-19 Stories from the Field series. We will continue to share personal stories from millennials who are essential workers, caregivers, and those close to them, as long as the pandemic continues.

Subscribe to the YMyHealth newsletter to stay up to date on everything that’s health-related for millennials!