The Difficulties with Diagnosing POTS

Written by Melissa Schenkman, MPH, MSJ

When Sarah Diekman, MD, JD, MS, MPH, was growing up, she always felt this innate desire be healthier, even though she thought she was healthy. Looking back at her childhood, she thinks her quest for health was really rooted in the fact that she had always been sick and told she was not.

It’s a common theme amongst people living with Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome, known for short as POTS, one Diekman had firsthand and finds in the patients she now treats who are living with her same condition and other forms of dysautonomia.

“I actually have always had symptoms but was told that my ‘symptoms’ were just personality or character traits of mine,” Diekman said. “When I talk with patients, and we look back at their childhood, they will have usually had either headaches, stomach aches, or fainted very easily, but their symptoms were at a level where they were not debilitated by them.”

Rather, she said, “They could make minor modifications. So, everyone around them would chalk them up to some personality traits.”

POTS is a form of dysautonomia, a disorder of the autonomic system—a highway of nerves throughout your body that actively and automatically at all times controls our heartbeat, breathing, blow flow, and other functions.

In POTS, the body’s blood flow becomes dysregulated, so that when a person stands upright blood pools in the legs and not enough blood is pumped back up to the brain and heart. This leads to lightheadedness sometimes with fainting, heart palpitations, tremors, nausea, and other symptoms. Currently there is no cure.

POTS affects an estimated at least 6 million Americans, and the number of diagnoses in young people continues to rise due to increased physician training and awareness, and cases related to Long COVID (currently estimated at an additional 3 million).

Ironically, Diekman diagnosed herself during what is already one of the most challenging and stressful situations in life—being in the midst of medical school. Sadly, she received zero support or even acknowledgement of the significance of her symptoms from her “educated and fully trained” physician-teachers. Instead, she finally landed a diagnosis from a board-certified physician, in addition to herself, after doing research and having to fly across the country to a well-known medical center to get one.

Diekman takes us on her own journey, shedding light on why diagnosing POTS can be so difficult–from the vagueness of symptoms to the amount of self-advocacy millennials and people of all ages, especially women, need to have to get a proper diagnosis and treatment.

Plus, she highlights the lack of knowledge by so many within and outside the medical community still to this day—something she changes in her own practice, Diekman Dysautonomia LLC, one patient at a time.

Lack of awareness

While the knowledge of POTS existence in the medical community is rising due to a number of educational efforts by patient advocates and advocacy organizations alike, it has been a long battle to get here and is far from over.

Healthcare providers, in particular primary care physicians, who are generalists, often misdiagnose patients who have POTS. Diagnoses that have mistakenly been handed out in lieu of POTS include anxiety disorder, depression, even bipolar disorder, ADHD, chronic fatigue syndrome, and irritable bowel syndrome.

Meanwhile, people come to their healthcare providers looking for answers after feeling like they are going to pass out or be nauseous if they do not lie down, and this is happening multiple times a day.

“People will try and rationalize these things. POTS wouldn’t even be on many physicians’ radars,” Diekman told me.

Even worse, when she went to see her primary care doctor to seek answers for her symptoms, he wanted to know, ‘What does it matter if we give you a diagnosis?’

Her answer: “It gives you absolute predictability. It gives you the ability to know your treatment options, find ways to modify your life to have the highest quality of life possible, and legal protections.”

That’s something that would have been exceptionally helpful to have in medical school, where, as her symptoms became increasingly more debilitating, she was unfortunately met with the attitude from multiple professors that she was a drag on the system because of her medical issues and did not belong there.

How wrong they were, as it was through Diekman’s own knowledge and research, and advocating for herself that she made her own diagnosis of one of the most complex medical conditions in existence.

Sarah Diekman, MD, JD, MS, MPH, is a Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS) and Dysautonomia expert who is board-certified Preventive Medicine physician. She uses her training as a physician and experience as a POTS patient to treat fellow dysautonomia patients in her private practice, Diekman Dysautonomia LLC. Simultaneously, she is an Instructor and Adjunct Professor at University of North Carolina Grillings School of Global Public Health.

Diekman earned her MD and her MS in Biology/Biological Sciences from Indiana University, She then went on to pursue and earn her JD at Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University. She did her residency in Occupational and Environmental Medicine at Johns Hopkins University, where she was Chief Resident. She earned her MPH at the John Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Vague symptoms

One of the immense challenges of diagnosing POTS is how vague symptoms are. If you combine that further with being in medical school or in any other very stressful situation in life, it’s a recipe for disaster to be able to get proper treatment.

“In medical school there is no time to take care of yourself and you’re going through all kinds of environmental stressors, including decent exposure to some allergens like formaldehyde,” Diekman said. “It is so hard to tell where your fatigue is coming from when you are in situations where everyone else is fatigued.”

Her initial very out of the ordinary symptom was coughing to the point of where she felt like she couldn’t breathe. Her breathing problems became so concerning at night that she slept on a friend’s couch, who was a surgical resident, so he could give her tracheotomy in case she woke up choking in the middle of the night.

She sought medical care for these symptoms and had a test to diagnose them three times, but all three tests were read incorrectly. After ending up in a pediatric ER once, it was there that they finally suggested the right diagnosis of vocal cord dysfunction. She saw a laryngologist and finally got proper treatment.

But it turned out to be just one of her mystery diagnoses. Although, she learned later that there may be a correlation between vocal cord dysfunction or what’s called irritable larynx syndrome and POTS.

Then, she was fainting multiple time a day, and over time she began to experience severe deconditioning to the point of not being able to do anything and losing half her body weight (down to a size double zero at 5 foot 8 inches tall).

“To put it in terms that perhaps give people the scale of what I was dealing with…I have four graduate degrees. I have been through law school and medical school, and making ramen noodles during that period of my life was harder than all of that,” Diekman said.

She thought it was related to the vocal cord issue or maybe she was depressed, but her bachelors degree in psychology saved her from that diagnosis, as she knew she didn’t have depressed thoughts or any other depression symptoms, and still had motivation.

She went to the ER, thinking she had POTS for sure at this point, and begged them to diagnose her. Instead of POTS, they diagnosed her with an eating disorder. Wrong. After doing some research, she flew across the country to see a cardiologist at Mayo Clinic in Arizona.

She did not say a word though about what she thought her diagnosis was when the cardiologist walked in the room. After examining her thoroughly, he looked at her and said, ‘Have you ever heard of POTS?” Shortly after, she finally received her official diagnosis.

“It was very life changing because having a diagnosis makes a difference. You can really start to narrow down what’s going to cause a flare up,” Diekman said.

Variability of symptoms

While POTS at its core is when “the blood that should be in your brain is in your legs; and your heart is pumping faster to try and get it back up there,” as Diekman describes, there are so many different ways that can play out in the way a patient presents. This variability of symptoms is why it is so tricky and can take so long to get a POTS diagnosis.

When not enough blood is getting to the brain, the body signals the release of adrenaline, which causes the blood vessels to constrict and maintain blood flow. In the case of POTS, it’s a massive release of adrenaline. That said the brain, has multiple additional ways it can respond, which is why the combination of symptoms people living with POTS experience can be so different.

A person could experience presyncope, where they have the feeling that they are about to pass out or are going to be nauseous unless they lie down. Another person could not get as lightheaded, but have a very fast heartbeat, and feel very sweaty, shaky, and anxious, she told me. Some people living with POTS will have their blood pressure drop if they lay down and for others it will remain high.

“People are usually experiencing all of these things, but on different levels, one symptom dominates and overshadows the others,” Diekman explained. “Dysautonomia is this large umbrella and underneath that is orthostatic hypotension, POTS, and sometimes patients have dysautonomia symptoms but don’t fit a specific syndrome. When that happens, the diagnosis will be dysautonomia NOS or dysautonomia unspecified,”

Another thing in the mix, that she has found really important to consider is whether or not someone also has Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (a connective tissue disorder) or mast cell activation syndrome because of different things like changes in diet for mast cell can make people feel better.

“If you treat people with dysautonomia, you need a resilient mind because every patient, every person is different. And just when you think you know the rules, you will be humbled,” Diekman said.

POTS Symptoms Checklist

According to Dysautonomia International and multiple reputable sources, here are some of the common symptoms of POTS that patients can experience:

Rapid heart beat

A drop in blood pressure upon standing

Hypovolemia (low blood volume) and high levels of plasma norepinephrine (a hormone and chemical messenger that increases your body’s “fight-or-flight” response which increases your heart rate etc.) while standing, reflecting increased sympathetic nervous system activation

A small fiber neuropathy (nerve damage or disease) that impacts their sudomotor nerves–the autonomic nervous system’s control of your sweat gland activity (50% Of POTS patients have this.)

Fatigue

Headaches

Lightheadedness

Heart palpitations

Exercise intolerance

Nausea

Diminished concentration/ ”brain fog”/perceived cognitive impairment

Tremulousness (shaking)

Syncope (fainting)

Coldness or pain in the extremities

Chest pain

Shortness of breath

Development of a reddish-purple color in the legs upon standing, believed to be caused by blood pooling or poor circulation.

**Please keep in mind that not all patients with POTS experience all these symptoms.

Lack of objective testing

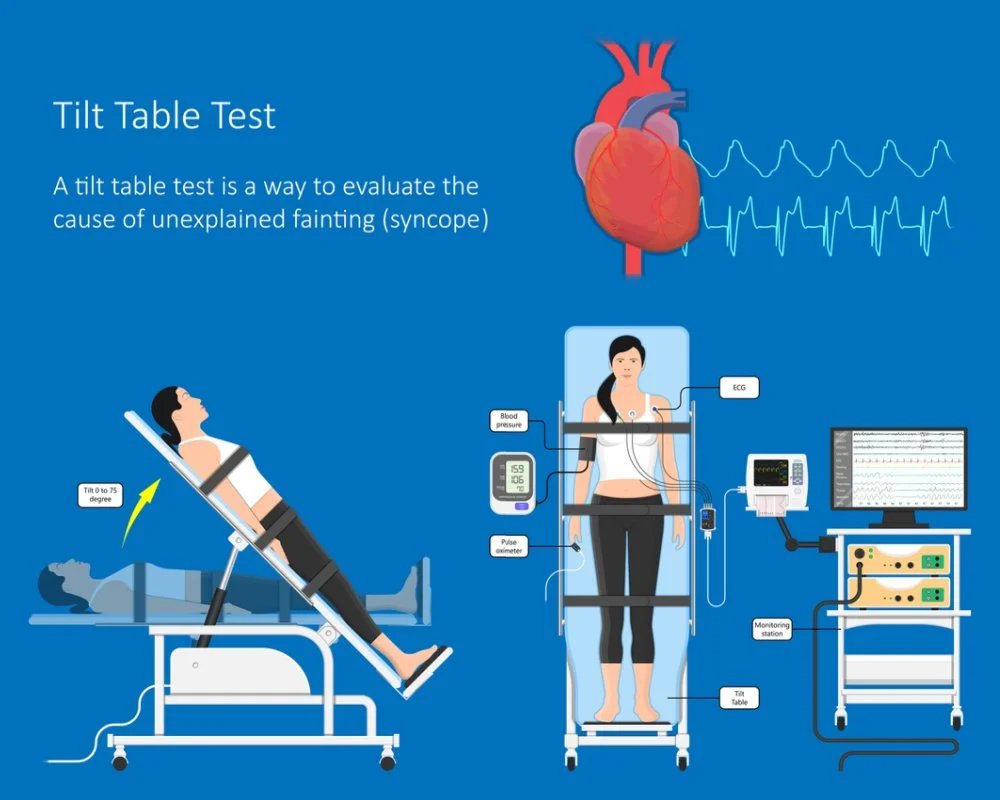

As of now, the main way POTS is diagnosed is by taking a tilt table test. This positioning imitates what happens to the body when you stand upright after lying down. Currently, the diagnostic criteria or test results required for a diagnosis of POTS are: a heart rate increase of 30 beats per minute or more while on the tilt table without having orthostatic hypotension (low blood pressure that occurs upon standing after lying down or sitting).

However, Diekman told me that specific criteria are pretty controversial. She has seen patients have a heart rate of 30 beats per minutes at the 11-minute mark on the tilt table. So, they are not considered to have POTS because of the way the tilt test is read, yet everything about the way they respond to treatment, and everything about their life indicates they have POTS or another dysautonomia.

She believes that eventually the diagnostic criteria for POTS will become broader because there is no difference between the way a patient who has 30 beats per minute at 10 versus 11 minutes responds to treatment.

Comorbidities

There are several conditions that can go hand-in-hand with POTS or are also known as comorbidities. They are:

Hypermobile Ehlers–Danlos syndrome and hypermobile spectrum disorder

The impact of a delayed diagnosis of POTS on patients' lives

When Diekman was a child, her parents responsibly took her to the pediatrician, and she even had a tilt table test, but she was never diagnosed with POTS. Now she knows the test clearly must have been read incorrectly.

The long road to receiving a proper diagnosis with POTS for her and so many other patients impact quality of life significantly, especially the longer they have to wait.

Unrecognized symptoms can lead to deep childhood injuries and as the years go on, the self-esteem of undiagnosed patients takes a nose-dive because despite feeling terrible, no one in the medical community is validating their concerns or seeking additional testing to get to the root cause as they continue to suffer. This can take years to recover from.

On top of that, the fear from their symptoms and not knowing when they will strike next or why they are happening, impacts a person’s day-to-day professional and social life drastically.

Remember, Diekman was in medical school and sleeping on a surgery resident friend’s couch, so he could save her life during the middle of the night, if needed.

Dr. Diekman on one of her shifts during her residency at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

Tips for patients seeking a diagnosis of POTS

If you or someone you know has been experiencing symptoms that you think are related to POTS, here are some of Diekman’s tips for getting a diagnosis:

Seek out care from a doctor who is familiar with POTS. Do not listen to doctors like the primary care doctor who told her: “What difference does a diagnosis make?”

Ask about mast cell activation syndrome, as she believes that can have a huge impact on POTS, if you have it. (Even though, she says she is in the minority of dysautonomia doctors who believe in this connection.)

Once you are diagnosed, get a therapist. They will help you to role play conversations about how to draw boundaries with people, as you navigate your symptoms.

How to advocate for yourself and get the care you need

At the end of the day, the most important thing is to always be your own advocate for your health. Without self-advocacy in the face of a complicated diagnosis like POTS, Diekman and so many others would never have received the answers or treatments they needed.

There are three ways she has found advocating for your own health can get patients living with POTS the care they need.

First, know that you have legal rights in the workplace. Learn about the Americans with Disabilities Act. It guarantees that every employer follows their legal obligations to provide workplace accommodations, including time off from work to go to doctors’ appointments and get care. It’s important to understand your rights and that you do not need to ignore your rights to care and accommodations in order to be a good worker.

Second, spend your time and energy strategically, so that you can enjoy things in life that are important to you, and limit how much your health suffers in the process.

“I tell my patients it’s like a spending account. So, I don’t do something that’s going to flare me before my best friend’s wedding. Instead, I go into lockdown mode a week before something super big like that and give myself downtime afterwards,” Diekman said. “If there is something important to you, then make a plan and do it.”

Finally, use your voice. After enduring so much ableism (discrimination in favor of able-bodied people) in medical training and having people make her feel ashamed of being sick, Diekman has gone the opposite way. While it has been a huge learning experience and is a constant evolution, she has learned to embrace POTS and want to be a role model for others.

“I was told that I should basically go home and die, not to ask for accommodations so I could work but also not to go on disability,” said Diekman who holds an incredible four graduate degrees, treats patients, and is a professor. “I do not want terrible people who say those kinds of things to do it to the next person, so I will not shrink or be ashamed of my illness. I view it almost as my role to be loud.”

Dr. Diekman at the 2023 Dysautonomia International Annual Conference in July. Not only was this her first time attending in person, but it was also her first time there as one of the conference’s speakers. Dysautonomia International is a nonprofit organization that works to improve the lives of people autonomic nervous system disorders.

Conclusion

POTS is one of the most complex and challenging medical conditions to diagnose, and being a young person seeking a proper diagnosis does not make it any easier. By familiarizing yourself with the many different symptoms and ways POTS can appear and following Diekman’s advice on advocating for yourself, you can be armed with the resources you and your friends need to get the care you rightfully deserve.

Subscribe to the YMyHealth newsletter to stay up to date on everything that’s health-related for millennials!